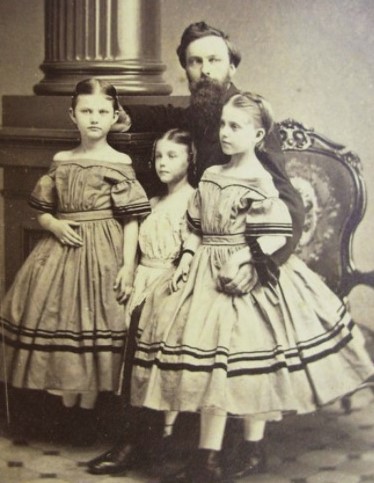

Have you ever seen a picture like this in a book?

Or saw re-enactors wearing all black in the sun?

Have you thought, “Why did they choose to wear that?”

Look no further than this blog for an exploration into why (and how) our female ancestors dressed in such fashions.

Things to remember:

- The Civil War years were 1861 to 1865. It’s a small window of time, but fashion went through huge changes as people were denied goods and services they were accustomed to having.

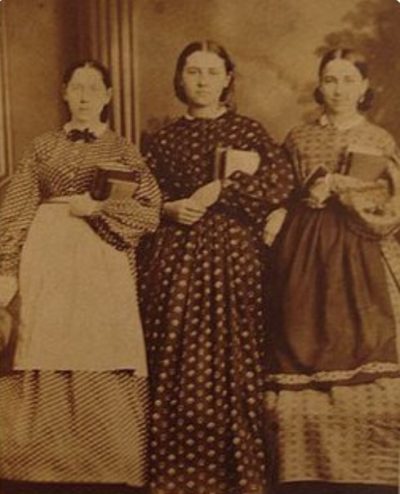

- This was a period when the normal person had two or three garments, with the nicest being reserved for Sundays, church services, and pictures (which were expensive and, on average, taken once or twice in a lifetime).

- Before the war, it was most common for dresses to be made from cotton. Once the war began, northern states had cotton shortages because the South was blockaded, and excess cotton was shredded to make bandages for soldiers. This made fabric for new dresses expensive and difficult to obtain. Old dresses were repurposed with hemming, patches, and worn until the seams gave out.

- The rightmost dress in the photo below is altered. It has been lengthened as the hem is much lower than the hoop. The apron is also patched with a piece of matching fabric.

- For most women, dresses were a generation behind the current fashions (1850s silhouettes still being worn in the 1860s). The newest trends were reserved for the rich who could afford more clothes, the best fabrics (like velvet and lace), and seamstresses.

The Process:

Yes, getting dressed was a process and clothing items had to be added in a specific order.

- Getting dressed began with the shift and pantaloons, aka underwear, which was cut down the center for bathroom use. Like most undergarments of the time, these were white. Underclothes were not meant to be seen, they were meant to collect dirt and sweat and then be scrubbed clean in the wash. Knowing this, it seems counterintuitive for these garments to be white. However, white was the lone color that could stand the washing process, which was harsh enough to remove the color from the fabric.

- Socks and shoes were added at this time since corsets limited bending.

- Next came the corset. Modernists have demonized the corset as being anti-feminist and restraining women. But the corset had a real job – and it wasn’t to restrict airflow. Tightlacing scenes like those in Gone with the Wind are exaggerated for film.

- The corset was an older version of the bra. It supported the back and chest, though it did not make the chest bigger, while also making sure the outer dress hung right and achieved the proper shape. Dresses were heavy. That weight was dispersed by the corset and hoop. Most corsets were white, sometimes with decorative colored stitching. Few were dyed as it was expensive and impractical. Unlike modern corsets, these were meant to be hidden, not to show off.

- Another common misconception about the corset was that it injured the wearer. Some movies and television shows have shown characters with cuts on their backs due to corsets. However, getting cut would not have been possible as corsets were never worn on bare skin.

- Then there was the hoop and its various covers. As with the corset, the hoop could not be washed because of its boning. It had an upper cover to prevent the bones from showing through the dress. Sometimes the cover was sewn to the hoop. These were known as flounced hoops and were usually worn for special events. Since the hoop was closer to the ground and collected dirt, it also had an undercover. More covers, or those made of heavier fabrics, were added in colder months for warmth.

- Now onto the dress itself. For women, day dresses fastened in the front. Evening dresses laced in the back. Outer clothes could not be washed, only hung to air out. Dirt would have to harden to be brushed off. This was why you did not wear your best gown to do chores. Even rich women wore plain clothes if they were somewhere like a camp or base hospital, due to the high risk of encountering dirt, blood, or open flames.

- Hair was finished next, if not already completed. Hair was worn up, parted down the middle, and secured off the face in a snood – sometimes made more fashionable with the addition of a ribbon. Little girls had the option of wearing their hair down if they wanted, though even children were photographed with their hair up.

- Accessories were added last. Depending on where one was going, these could include earrings, bonnets, gloves, brooches, and necklaces.

- Earrings were always dangle-style. Studs were not in fashion at this time.

- Head coverings were required outside, sometimes with a veil attached to ward off dust.

- Thicker gloves were used for riding and cold weather. Softer gloves were worn in the summer months and as a symbol of class. Interesting fact: Abraham Lincoln was known for putting his gloves in his pocket when it was warm, despite his wife’s insistence that he wear them to show their status. In the pocket of his coat were where his gloves were found after his death.

In comparison to these “wild” outfits, our modern clothes seem to have come a long way since the Civil War. However, the fundamental principles of fashion remain the same. We still strive to look our best, overcome the weather, and use what resources are available for every advantageous pursuit. Our versions of corsets and gowns may look different but they are still creations connecting us to our ancestors.